The birthing process of a book is... well, a process. It starts with the seed of an idea, goes through story development, into a first draft, followed by many rewrites, and then hopefully, eventually, it makes its way into the world, into the hands of readers.

Today a special book hits the shelves: Sushi Tuesdays: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Resilience by Charlotte Maya. I have been privileged to be on this book birthing journey with Charlotte through the story coaching and editing process, which she shares about in the video below. It is deeply rewarding to support a book that I know will affect the hearts and minds of those who read it; a book that handles the very difficult subject of suicide with remarkable skill and humanity.

The book launch event for Sushi Tuesdays is taking place this evening at 7pm at Vroman's in Pasadena (offsite venue: All Saints Church). Come join me!

Scroll down to read my interview with Charlotte where she talks about the writing life and what it's like to work with a publicist in preparation for her book launch.

Charlotte Maya writes about suicide loss, resilience, and hope. Widowed at thirty-nine, when her children were six and eight, Charlotte explores the intersections of grief, parenting, and self-care in her writing—particularly within the context of suicide. Her work has been highlighted in Hippocampus Magazine and The New York Times. Sushi Tuesdays: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Resilience is her first book.

Charlotte lives in Southern California with her family. She received her B.A. from Rice University and her J.D. from UCLA.

Read Charlotte's Modern Love essay When A Doorbell's Ring Means Hope.

In the above video, Charlotte Maya shares about her experience through the Story Coaching process. Learn more about one-on-one story coaching.

KARIN GUTMAN: Tell us about the story behind your debut memoir Sushi Tuesdays.

CHARLOTTE MAYA: The short story is that I was widowed to suicide when my kids were six and eight. I had no idea that Sam was suicidal. So, a large part of the story is trying to figure out where I had failed him, where he had failed himself, and how to heal and move forward. It was really important to me that his death didn't define my life; but then it was impossible for it not to. I did accidentally fall in love again. My now husband had also been widowed and has two kids.

As far as crafting the story, it was really important to me that the book didn't end with a fairytale ending because, in my opinion, the grief doesn't really end. There's not a point at which you're done. It's important for people to understand that even though we are living lives with joy and passion and the kids are doing well, we all have our struggles. This kind of loss reverberates, and in some ways, changes who you are. We simply continue to carry that loss with us in a way that doesn't hamper our forward movement. But we don't forget, we don't get over it. We learn to carry it.

It's important for people to know that we do still honor Sam. He made a mistake, and by that I mean, he did not reach out for help. But how he died does not define the whole of who he was. I also had to get to a point where I realized I could continue to live my life in a way that honored myself and honored him. Part of that was becoming the writer who could tell the story.

KARIN: I know you started writing your story with a blog. How did you move from blogging to writing a full-length book?

CHARLOTTE: When I was writing my blog, I had all these posts. I printed them all out and had several 100 pages. I read it and it wasn't a book. I didn't know how to turn that stack of pages into a cohesive story. Then I heard a podcast where they said, “Just because you've read 100 books doesn't mean you can write one. That's why you need a book coach.” What I need now is a book coach, I thought. I was in your workshop and so that was easy for me to call you because I already knew you. I already trusted you.

I didn't have a journalism background. I had a law degree and an English degree. I hadn't ever contemplated being a creative writer. I didn't have an MFA. I felt like my work with you was a mini MFA. It was so exciting to learn about story structure and character arc and how things work. I enjoyed reading, but I didn't really peek under the hood.

KARIN: Suicide is a challenging topic. It feels to me like your story is coming out at a time when people are more open to discussing mental health.

CHARLOTTE: From the beginning, there was a feeling that I have a story to tell, and I believe people want to read about the story. Even though suicide is hard to talk about, and sometimes people clam up, my personal experience showed me that people really wanted to talk about it. People were always asking me questions, and they might say, “If you don't want to talk about it, that's okay.” But I did want to talk about it. Because I feel so strongly that talking about suicide is the way to reduce suicides and to reduce the stigma that surrounds not just the people who have died by suicide, but also those of us who are mourning the loss of somebody who has died by suicide. By destigmatizing, it opens up a place for people to be vulnerable and ask for help when they need it.

KARIN: You’ve described writing as a really expensive hobby. What have you spent money on?

CHARLOTTE: I've spent money on workshops. I've spent money on book coaches. I've spent money on writing retreats. I have spent money on building a website. I have spent money on hiring a publicist. I did not self-publish, so I did not spend money on that. I continue to spend money on workshops. I think it's really helpful for perspective. It can be hard to see out from the work and somebody else's feedback can be very clarifying. Offering notes to other people is also clarifying, like a muscle you exercise.

KARIN: How has writing affected your professional life?

CHARLOTTE: My husband and I have a business. I used to go into the office three days a week. Now I go in twice a week, and my other days are my writing days. I have been much more intentional about how I spend my time. I am not one of those writers who gets up and writes from five to nine. I have always prioritized my kids, and that's prime parenting time until they are off at school. My schedule is easier now that the kids are all launched or launching. Still, I will very rarely not answer the phone when they call.

But I am better at getting my butt in the chair and getting something done. I'm better at writing what is very drafty, knowing that it needs to be revised. Giving myself a little bit more space to get bad work done, because that counts. It all counts. I'm better at understanding that now. I feel like I now understand the process that I'm in, which parts I get to control and which parts I don't get to control. I get to control sitting down, getting something written. I get to control revising it. I get to control workshopping it with other people and revising it again. I can choose to submit it. After that, I've done my work. And so, I'm a little less attached to the result.

I'm getting better at being rejected. I think that's a good thing because it is less of a defining factor in whether I'm going to get my butt in the chair again. Validation is great and acceptances are thrilling. I'm not saying that they're not. But if those become defining, then the opposite is also defining, right? Not every piece of writing is for every publication, and that's okay. I always hope that the writing and the audience will find each other, but they are not things I can totally control.

It’s similar to why kids play sports. You can’t control the wins and losses. Wins come or they don’t. But the teamwork. That's something important that we take away with us. Doing your best, that's what counts. There's a lot of really good writing out there, that may or may not be on bestseller lists or on the tip of everybody's tongue.

KARIN: How long was the publishing process for you?

CHARLOTTE: I sold it in February of 2022. When I signed the contract, my editor said, “I want books in hands this time next year.” And she made it happen. My impression is that there are a lot of things that can slow down the book, from signed contract to completed book on shelves. We were able to stay right on track with deadlines all the way through, but even so, I think it's lightning speed.

That also informed some other decisions. She wanted to go straight to trade paperback, which we did. That's something I hadn't really thought about—hardback or paperback? She had some strong feelings, because she wanted the book to be accessible and paperback is cheaper to produce, and as a result, more affordable for buyers to purchase. That was really important to her. And it has always been important to me, so those kinds of decisions were very straightforward for me

KARIN: With regard to the book launch, what are you excited about and what are you nervous about?

CHARLOTTE: I'm nervous about interviews. And I'm excited about interviews. I'm nervous about time limits, because I feel like we could talk for an hour and may only have 10 or 15 minutes.

KARIN: Is your publicist helping you prepare?

CHARLOTTE: Yes, she does help with a media training session.

KARIN: What is it like to work with a publicist?

CHARLOTTE: I didn't realize that I needed to hire a publicist of my own, and that in and of itself felt a little disheartening, because I didn't understand why the publisher didn't cover that base. The publisher does do quite a bit. They send the manuscript out for reviews and get it in their catalogs and get my Amazon author page up. So, there's a lot of behind the scenes work to connect the book to potential readers. I hired Kim Dower because she has a lot of experience in LA, and it made sense to me to have a Los Angeles publicist.

I did not realize that you have to pitch your publicist, the same way you pitch an agent and a publisher. They all wanted to read the book first, before deciding whether or not to work with me. So that was a little intimidating. It makes sense because you want a publicist who's going to be on the front lines of trying to get people to read this book, trying to get people to schedule an interview. It made sense afterwards, but I was surprised they got to decide if my book was good enough for me to pay them. I think it's especially hard for a first-time writer too, because I don't have a built-in audience. I have a couple hundred followers. I do not have a big platform.

KARIN: How does the publicist work with you as the pub date approaches?

CHARLOTTE: She now has my calendar, and she is the one who has scheduled different podcast interviews or radio interviews. She put together a press release, which she has used to place advertising in different news venues and get people interested in hosting an interview. So, I have several interviews scheduled now around publication date.

She's very straightforward about setting expectations and really good at bouncing ideas off of too. I graduated from La Cañada High School, and in fact graduated from high school with the person who now owns the local paper. So, I said, “Should we send the press release to the local paper?” and she said, “That's a great idea. I'm on it.” So, today's paper has a little blurb in it. That's the kind of thing that I wouldn't have known how to do by myself.

Having a publicist also gives me a certain level of credibility. Because she has read the book, she has perspective on how it fits into the larger world of books. My publisher has so many books that they're working on, and publicists tend to only take on a few clients at a time.

KARIN: Whom do you imagine to be your ideal reader?

CHARLOTTE: People often tell me that they want to send my book to people who have lost someone to suicide. And while I hope that it resonates with those people, I really hope it resonates with people who don't have such an intimate relationship with suicide, but are open-hearted enough to want to learn about it. I think it will actually be more helpful for people who haven't had an intimate suicide experience, because I think it will take a lot of the fear and stigma away from understanding that suicide is just like any other illness. It just looks so much uglier from the outside.

Suicide is a disease. I hope that readers come away from this book with a renewed appreciation for all of our shared humanity. That it humanizes Sam, that it humanizes me, and gives us all space to be glitchy, beautiful people.

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

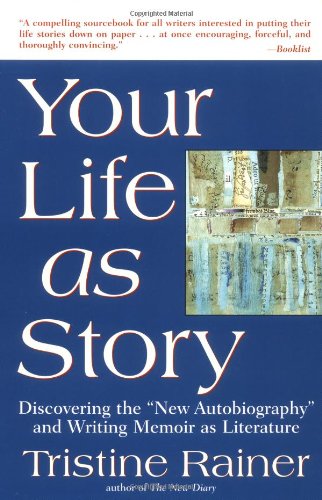

Buy the book

To learn more about Charlotte Maya visit her site.

See all interviews