This month I have the great pleasure of featuring my uncle, Bill Eshelman - a retired General of the Marines, whose memoir Letters to Pat just hit the shelves! It captures his time serving in the Vietnam War using the letters he wrote to his wife Pat over the course of that year, 1967-68, as the foundation of his narrative. Originally, he says, it was just meant to be for friends and family, but then with some prompting, he reached out to a publisher who believed his personal testimonial has a broader appeal and audience. I feel so proud of him for committing his experience to the page and am honored to share his story with you!

Bill Eshelman graduated from the US Naval Academy and served 35 years as a Marine, retiring as a Major General in 1994. His career covered many different command and staff positions, but it was during his time as a military advisor to a South Vietnamese infantry battalion in combat that he recorded his actions and thoughts on an almost daily basis in letters written to his wife.

Letters to Pat chronicles the day by day events of Bill Eshelman, a young Marine Captain writing home to his wife. Hoping to command a U.S. infantry company in combat, Eshelman is instead ordered to advisory duty with a Vietnamese Marine battalion. The ensuing months present new challenges: dealing with US headquarters, the Vietnamese way of doing things and contact with the enemy. The letters plus notes from his combat journal form the basis of his book written 50 years after his 1967-68 experience.

Karin Gutman: I never imagined interviewing you for a book!

Bill Eshelman: I've never imagined you interviewing me either.

Karin: Did you ever imagine writing a book?

Bill: No. This is the only book I've ever written. The way it started was, after the war was over and I was back in the States—so we're into the '70s now—then until now, whenever the subject of Vietnam came up people would say after we talked for a bit, "Why don't you write a book about that?" I had never thought very much about it, but I kept getting those questions, even from my kids. But more so from my friends and in particular a couple of my Marine friends that I had served with said, "You need to capture what the Vietnamese Marines did over there. Hardly anybody writes about the Vietnamese Marines. It's all about the U.S. Marines."

I'd think about it and say, "Well I don't even know where to start for that." And then I think it was December 2017, Christmas, I was at [my daughter] Cathy's home in Colorado, and for some reason, the subject of writing a book came up again. And she said, "You need to do this for the family." She pulled out this box of letters… they were the letters that I had written to [my wife] Pat. Pat had saved all of them.

Karin: Wow.

Bill: I was aware of the box, but I'd never looked at it or opened it over all these years. I didn't know she had saved all those letters. I opened up the box and looked at a couple which I hadn't seen in almost 50 years, or even thought about, and I got to thinking, “It's been 50 years since I was there. Maybe it's time.”

Cathy said, “Take these letters with you and see what you can do.” I brought them back here to Pensacola and spent all of 2018, a week at a time, going through those letters day by day and then pulling out of the letters what I thought was relevant about the war and my thoughts on it. And then I located my combat journal that I had kept the year that I was over there, '67, '68. And I added addendums to each of the letters when I thought it would help, based on more detail that I didn't write home to Pat about but was in my combat journal.

The more I got into that, the more I thought, “You know I need to finish this.” And so I took the whole year, and I finished it in December 2018.

Then I went back and added my thoughts, now that the war was over and all these years have gone by. We know so much more now about the war than any of us ever did when we were over there. Back then we only knew what was being told to us or what we were experiencing firsthand. There was no television and we had no access to the news every night. We were just living life an hour at a time at some points.

I wrote an epilogue at the end trying to pull together all the thoughts that I had had from those letters in the way I was thinking back then and what I know and think now. That's how I end the book.

Then I told the kids that I've put this thing together and asked, “Do you want me to run some copies off for you?” I think it was Cathy in particular who said, “No. You need to publish this thing.” I said, “I don't even know what that means.”

So I started asking around. It turns out my next-door neighbor here in the condo had done some work in that area, and she recommended two or three publishers to me. I picked out one that had a reputation for publishing a lot of military kinds of books in Virginia Beach. So I got hold of them, and I said, “I'd like to send this to you. See if you're interested. I just wrote it for my family and friends and they came back and said, 'We think it's got a wider appeal.'” And that's how it started.

Karin: How many letters were in that box?

Bill: That's a great question. I should've counted. Sometimes I would be writing a letter every day for a week or two. And then other times, it was impossible for me to write because we were on the move or in a battle, or it was raining; we were in the muck. That whole year I was on the move—or my outfit was on the move—so it wasn't like we went back to the same place every day. Lots of times the place I went back to was a hammock I hung between two trees out in the jungle or things of that nature.

So sometimes it would be as long as a week between letters. But for the most part, it was almost every day, so what 365 days? I probably have 150-200 letters.

Karin: That's amazing. So you were deployed for 12 months?

Bill: It was a 12-month tour, October '67 to October '68.

Karin: Did you know at the time that it would be for a year?

Bill: Yes, I had already been overseas for a year in Japan before Vietnam started. In fact, the reason I didn't get over to Vietnam until 1967 is I had just come back in 1964 from a year by myself in Japan.

And of course, the war really kicked off in '65. So they gave me a couple of years to get to see my family again before they sent me over to Vietnam.

Karin: And the letters you include were specifically the ones you wrote to Pat?

Bill: Yes, but I did write letters to my mom and dad and other people occasionally. But I don't have any of those. I only used the letters to Pat. And they were the most important because I was trying my best to write to her about what I was feeling, what I was going through so she could sort of live it through with me. She was home with three small kids reading the newspaper and listening to the news every night. And I can't even imagine how scary that must've been for her because it was taking one to three weeks for our letters to go home and come back.

There were no iPhones, no computers, none of that stuff. It was just snail mail. And sometimes, I was in a situation over there where I couldn't figure out even how to get a letter somewhere where it could be mailed. So I'd wait 'til a helicopter came in for whatever, hand it to the pilot and say, “Would you take this letter back and get it mailed for me?”

Karin: Could you actually read them after all these years? I mean, the writing hadn’t faded?

Bill: All the letters are readable, even those that got wet before I could mail them! They were written in ballpoint.

Karin: On a legal pad?

Bill: All kinds of stationery. I would try to keep some in a little plastic bag with me so they wouldn't get wet, a pad of stationery with some airmail envelopes. But there are all kinds of envelopes in the stack of letters. It's whatever I could find.

Karin: I'm curious to learn more about this combat journal…

Bill: It was a requirement. I had to make reports after every battle and every time period that had been established. I had to report back the numbers: how many wounded, how many killed, where we were, what the objective was. We who were officers or in charge of anything had to submit these back to the higher headquarters and that's how they reported the war overall.

One of my big gripes, and it's in my book, is that an awful lot of that was inflated as it went up to higher headquarters. And it was just a real problem for the outcome of the war.

Karin: What was inflated?

Bill: The numbers, especially the numbers of the bad guys. I'd go through a battle and knew what had happened because I was there. We counted the people that were killed and wounded on both sides, and counted all the weapons that were captured. And these numbers were reported up the chain of command.

In some cases, I even had a little camera in a plastic bag with me sometimes so that I could take pictures. And then Pat would send me a newspaper clipping which I'd get two or three weeks later from the Washington Post, and I'd read about the battle. Well, it was hard to tell that was the same battle that I had been in because the enemy numbers had all been inflated to make us look good—make us, the U.S. look good.

So early on as a young guy over there, I knew there was a little bit of a problem here. We weren't being really honest in terms of our reports.

Karin: How did you shape the letters into the form of a narrative that would work for a book?

Bill: Well, I added in the letters to Pat a lot of my own emotion that I was feeling as these different things were happening from day to day and from battle to battle. Somebody else came up with this phrase, but I use it because it's very descriptive… that that year over there in Vietnam, or in any combat zone I guess, for me and I think for most people if they're honest, could be described as days and weeks of sheer boredom interrupted by a few moments of stark terror.

That’s the way I wrote the letters back to Pat. When things would go crazy, I wouldn't write for a while because it'd take me a while to get my act together. And then I'd just give her the outline of the stark terror part. But all the details would be in my combat journal.

If I had time just to sit there all afternoon and think about it, I'd have a lot of personal stuff in there. If I didn't, I just wrote her, “Boom boom. Here's what's happening right now. I got to go. We're taking off again.” Stick it in an envelope and hand it to a helicopter.

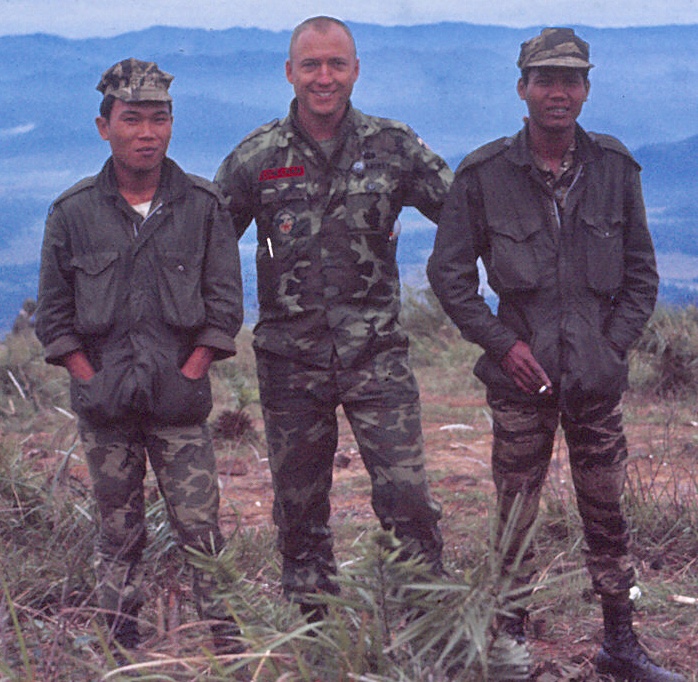

1967, Bong Son

1967, Bong Son

Karin: So once you had a draft of the manuscript, did you share it with anyone before going to any of these publishers?

Bill: Oh yes. As I wrote the first few months, I would send chapters to the kids and ask them if they have time to look it over and see if they had any comments or, “Am I going in the right direction for something the family might want to hold onto?”

I got pretty good feedback from the kids. I did it with a few of my friends around here too that I've known for almost 20 years. And I even shared it with a couple of folks back in Arkansas that I had stayed in touch with, that I had grown up with since first grade. So I had a pretty wide audience to bounce this off of including some of my Marine friends that I had served with at various places. But I never shared the whole book, just the chapters as I was writing.

Then my next-door neighbor who recommended the publishers to me, since she had had some experience in the editing and publishing business, said, “When you finish with what you've got there, if you'd like, I'll be happy to look it over and give you some thoughts on it.”

So around Christmastime last year, I handed a whole manuscript to her, and I said, “Here it is in the rough.” She took a couple of weeks or so, brought it back and pretty well liked what I had written. She just suggested that I might want to say this or that slightly differently and that was about it. But it was a great page by page edit.

Even when I sent it to the publisher and they put their editor on it, all he really did was change around a few sentences.

Karin: How was the experience of writing it for you?

Bill: It was emotional. As I said, I took a year to write this book week by week. And sometimes I'd read a letter, and I'd have to think a day or two before I could actually write it down and add to it from the combat journal. It wasn't something that flowed. I had to take myself back 50 years to make that thing work.

When I left Vietnam, we went to Thailand for two years, so I was away from the U.S. for almost three years. My orders were from Saigon to Bangkok, Thailand. So essentially I hitchhiked home back to Virginia. Pat had already sold the house, sold the car, sold the boat. And three days, later, we were all heading back cross-country and across the Pacific. And then I didn't return to the U.S. 'til the end of 1970.

As a result I wasn't exposed to everything that was happening back in the States. I missed the RFK assassination, Martin Luther King Jr., all of the anti-war rioting. I'd read about it in the papers, and you'd hear people talking about it from time to time, but I was wrapped up in my job. And none of any of that hit me full face until I got home the end of 1970.

We moved back to the Washington area, and wow, it was almost like I arrived in a different country. The attitude, everything had changed.

Karin: In what way?

Bill: ANTI-VIETNAM in capital letters. I was starting to get a feel for that while I was still in Vietnam a little bit, but nothing like in 1970 when we went back home again. So all that was sort of a turn-off for me; we didn't talk about Vietnam, especially with our civilian friends.

I remember a cocktail party at a friend's home in about 1971, I guess, a few months after we had been back. I'd known a couple of these guys since high school days; they were both married with families now. But we hadn't seen each other since high school up in the Maryland area.

One of the wives that I'd never known started to engage me in talking about Vietnam and I started to tell her a little bit. I mean, I just responded honestly. And she said, “You're a liar,” and it stopped the whole party. She said, “You're lying. You don't know what you're talking about.” Now I'm thinking, “She doesn't think I know what I'm talking about? I was there.” So I just let it go. But that's an example of what I came back to.

Karin: What were you talking about?

Bill: I told her that I had lived with the Vietnamese for almost a year. I said there's some good points, nobody's perfect. I can't remember the exact words. But it didn't include the kind of things, I guess, that were on the six o'clock news back then—that I was starting to hear since I'd gotten back. So those kinds of things did not give me any reason to think about writing a book.

Karin: So did you repress and bury the experience?

Bill: Those words may be a little strong. But it was that thought. “Yeah, I've got other things I need to concentrate on. If I'm going to stay in the Marine Corps, I need to concentrate on my job. And I don't need to let this bother me, that kind of thing.”

But I always kept getting comments every so many years from different people, “You ought to write a book about that,” whenever we started talking about Vietnam.

Karin: So when you decided to spend that year revisiting all of these memories and experiences, you say it was emotional. I can only imagine. Did you apply any self-care practices through the process?

Bill: I did. Sometimes I just had to put the letter down and wait a couple of days before I could finish that chapter. Yes, especially when I'd read the letter, then I'd read my combat journal, and get into the casualties and talk about some of the really bad stuff. It was better for me to wait a day or two and let it filter through rather than react to it immediately. And I found out it was much easier to write that way if I didn't rush it.

I didn't have any deadlines. I was just thinking about halfway through, “This thing is going sort of month by month just like I lived it 50 years ago. If this keeps up, I'll probably finish the book the end of this year.” And sure enough, that's the way it happened.

Karin: Did you at any point feel like, “Oh I don't want to keep doing this. This is just dredging up too much… too many memories, too many emotions.”

Bill: Just the opposite, Karin. The more I got into it, the more I felt like I've got to finish this. I need to do this for the kids and for my family. And I was not thinking of anything beyond family and friends.

Karin: And how about writing it for yourself?

Bill: I think it was always about my family and friends. I don't think I needed to re-live it again. It was pretty hard sometimes. But I did need to do it to finish the book for the family.

Karin: Where are you now, on the other side of it? Was the process of writing transformative for you?

Bill: How could it not be? I just can't tell you how much. In church, first week of September, the pastor has asked me to stand up at a Wednesday night dinner where they feature different folks to talk about their lives. And they want me to talk about this. And I wouldn't have done that a couple years ago, but I don't have a problem now doing it.

One of the reviews from a good friend of mine, a Marine friend of mine—he's retired—said something like this as he reviewed the book, “You said all the things that we were thinking about but never said ourselves.” And that really made me feel good.

Karin: That's got to be the greatest compliment.

Bill: I thought it was.

Karin: Now that your book is being shared with the world, what are you hoping the takeaway or message is?

Bill: Well, I guess I haven't thought about that very deeply, but off the top of my head, I'd like for families to understand what their loved ones are going through on a day-by-day basis when they're thrown into a situation like I was in, into a combat zone, which is still happening today as you know.

And the second thing I'd like for people to understand is the relationship with the third world country like Vietnam, and like so many other countries now that we're involved with. I'd like them to understand down at the ground-roots level where I was living with the Vietnamese, and most of the time by myself as the only American, what the challenges are and how that can just wear you out. The Vietnamese had been in this shooting war for a long time. It was just day by day trying to exist and make things work for them.

And that's what I was trying to explain to Pat in the letters. It's exactly what I was thinking back then. As I read a letter at a time, as I put this book together, I said, “That's right on.” And a couple times, I expanded on it just to emphasize it. That's all in italics in the book whenever I added to her letters.

I don't know that this book is going to be a success or not. I think it's going to be fun for my family and friends. But in terms of publishing a book to the world, I don't know anything about that yet. It might sell 100 copies, and then that's it. But that wasn't my goal, so it doesn't matter.

If it's successful, I think that's great because I think there's a story there for young Marines to read about and for families to read about. And it's interesting for non-military folks too if they want to get a sense of what military folks are going through and what the families then would have to be aware of.

Karin: It also certainly offers some perspective on the Vietnam War. Whether you're curious about what the families in the military go through or not, it's a personal testimony which is different, and perhaps more powerful, than a history book!

Bill: Yes, you're exactly right. The history component there is valuable, I think, because I've written it from the Vietnamese side during the 68 Tet Offensive which was one of the most horrific times... that was the turning point of the war it turns out, because everybody back in the U.S. thought we'd lost the war. Of course, I didn't find out about that until much later. I thought we'd won.

What I documented to Pat and in my military journal, and in some parts it's hour by hour for a few days, is how that battle went and how we won those battles during Tet 68. So there's a historical significance to this on the Vietnamese side that I don't think has been written about before.

Karin: Incredibly valuable. From your perspective at the time, why did you think we’d won the war?

Bill: Well, I was in three major battles over there during that year. We never lost a battle. We lost a lot of people, but we inflicted more damage on the North Vietnamese than they inflicted on us. In terms of numbers, we won every battle, so I had a hard time trying to understand when I'd hear from Pat or she'd send me newspaper articles about how we were losing after the 68 Tet Offensive. But I didn't think a whole lot about it. We just kept trying to win the next fight.

Karin: But I thought you said the U.S. papers were publishing better numbers?

Bill: No, the U.S. military was doing that. Saigon, General Westmoreland, and the Military Assistance Command Vietnam were inflating the numbers of enemy casualties as they were coming in and providing them to the White House and press. And I don't know if they were reducing the numbers of our losses or not. But they were certainly inflating the numbers of the battles that we were winning, and then that was going on the six o'clock news I guess to try to make us look like we were doing better than we were.

And then in the middle of all of that, with all these inflated numbers of how we're just winning this war big-time, the Tet Offensive happened, where at end of January and first of February in 1968, the whole South Vietnam exploded because the North Vietnamese had infiltrated over time the whole country. Like our New Year's here, we went on a truce where everybody stood down during the Tet which is their New Year's, and people went home. The Vietnamese went home. Everybody just took it easy. This was supposed to be a vacation for the North and the South. And the North then pulled the rug out from underneath us and attacked the whole country all at one time and caught us by surprise. Well, the papers back home made a big deal about how we got caught with our pants down and they created among us initially a whole lot of casualties. But we reacted and we fought back. And we won back every town and every hamlet that they had taken by surprise because they cheated on us. That's when the war turned around because the news folks back home, I guess, convinced a majority of the public that we were never going to win the war after that.

Karin: Now I understand...

Bill: But see that wasn't so evident to us there at the time. We had no six o'clock news. We weren't getting newspapers. I was primarily just hearing it from Pat from time to time. There were times that she could tell where I was and what was happening by reading the Washington Post long before she ever got a letter from me.

Karin: And now that you're done with the book, do you feel like writing anymore?

Bill: No, I don't. But I didn't feel like writing before, until it happened.

Karin: This is the story that needed to be told.

To learn more about Bill Eshelman, visit his website.