This month I had the good fortune to dialogue with author Madhushree Ghosh, whose debut food narrative memoir, Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey, is written using a braided structure, weaving the stories of her refugee Bengali parents, her own immigration from India to America, and South Asian chefs. We discussed diversity in publishing, dispelled some writing myths, and defined what it means to be a good literary citizen. Scroll down to read the full interview!

Madhushree Ghosh’s work is focused on food, immigrant journeys, social justice in particular, about women-of-color-in-science. Her work has been Pushcart-nominated and was the 2020 Notable Mention in Best American Essays in Food Writing.

She has a PhD in Biochemistry, and post-doctoral fellowship in molecular biology from Johns Hopkins University. She actively mentors emerging women leaders in science and works in global oncology diagnostics, based in San Diego.

Her debut food narrative memoir, Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey (University of Iowa Press, April 2022) weaves the stories of her refugee Bengali parents, her own move from India to America, and innovative South Asian chefs, and how they used food to recreate their worlds in a new place and maintain connections with their families and cultures.

KARIN GUTMAN: What is a braided essay or braided narrative, and how do you suggest a writer begin exploring this kind of structure?

MADHUSHREE GHOSH: I gave a recent talk at Muse and the Marketplace for Grub Street on this and here is a brief overview:

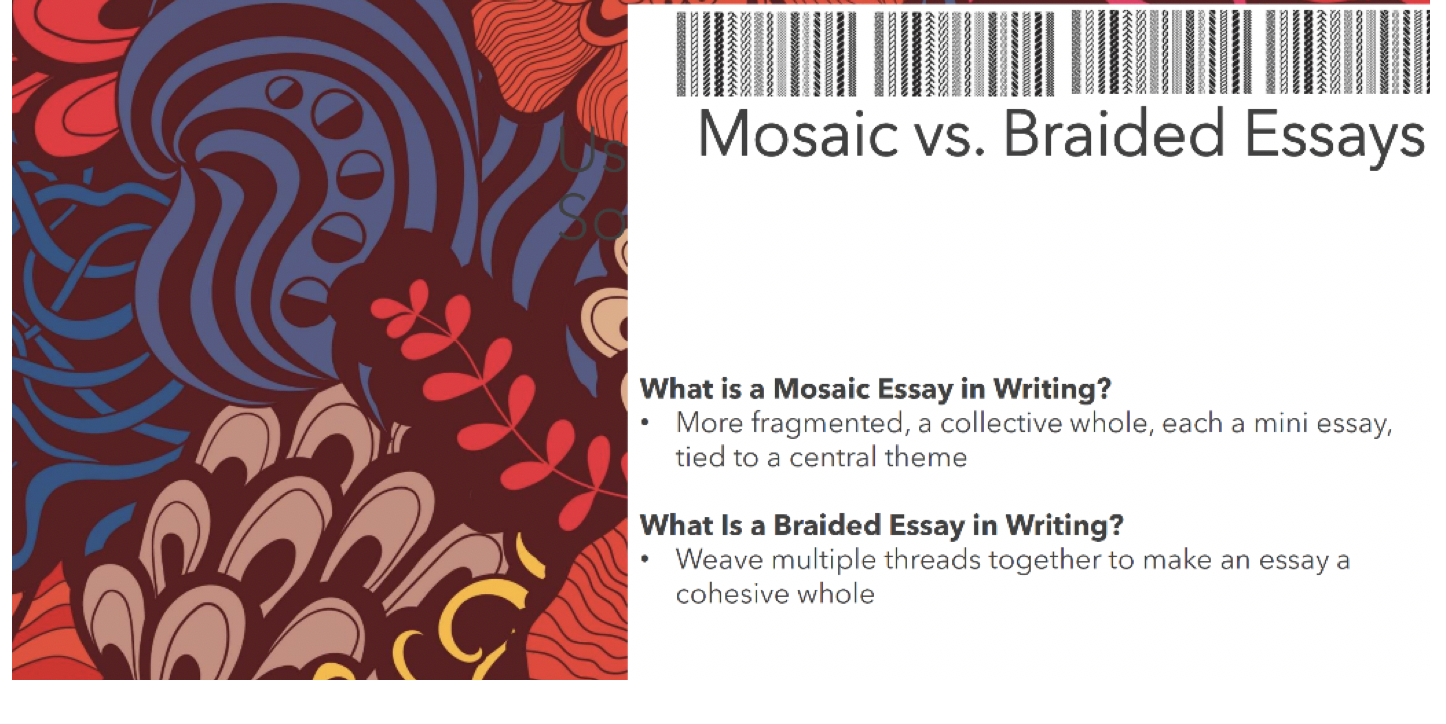

When you use fragmented threads—each with a narrative arc, a question, a reflection and a resolution or a hint of a resolution—tied to a central question or topic, it’s a braided essay. The resolution doesn’t have to be complete, but the need to align the separate threads needs to be.

A writer should first determine if there are commonalities in the threads, braid it to make the heft in each thread similar, and then ensure the narrative arc is prominent in both. One could be a personal thread and the other political or journalistic or analytical or a combination of all.

KARIN: What qualifies as a “diverse voice”? How has the shift in publishing towards diverse voices impacted you?

MADHUSHREE: The Lee and Low Diversity Survey tells me that there hasn’t been a big enough shift in publishing toward diverse voices. Yet.

Diversity as defined by all DE&IB entities (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging) is a combination of race, gender, orientation, disability, as well as thought.

Here is their data—pictures speak louder:

Publishing has NOT shifted to diverse voices—this data is from 2019. So no, a brown woman like me has not benefitted from this so-called shift because that shift hasn’t happened. I published my first book, a food narrative memoir-in-essays that took twenty years to get there. That is not a shift but a typical highlight of what we go through.

Whether it’s race, gender, orientation or disability, we are not there. It is time we acknowledge that instead of performative announcements that highlight that issue. The movement toward universality and diversity—of the four pillars (DE&IB) as well as that of diverse opinions and thoughts—is not acknowledged.

KARIN: What is literary citizenship? Why is it important and what makes you, Madhushree, a good literary citizen?

MADHUSHREE: If one is a writer, you are a writer for life. How would you acknowledge that and not make it transactional? In order to do so, one needs to read other voices. One needs to keep learning. One needs to passionately champion other writers. Even when one’s work gets rejected on a daily basis. Persistence and Passionate Championship of others should be everyone’s motto.

I’ve been doing this for decades—in life, in my corporate world and in writing. So it’s second nature to me. Sometimes you write reviews. Or interview authors (for me, it’s authors of color, debut authors especially who do not get the publicity they deserve). I talk about other people’s work on my social media platforms. I learn from them. I buy their books and I talk about the style, nature and work. I celebrate their successes. And I believe in their words—that’s just how a writer's life should be or try to be. There are many like me. I hope everyone does what I do because writing should be joyous. The life of a writer is mainly that of rejection. So celebrate yourself, others, and the journey. That’s what a literary citizen should be doing forever.

KARIN: Tell us about how many of your essays have been plucked from the infamous Slush Pile. Are there any other writing myths you wish to dispel?

MADHUSHREE: Quite a few of them actually. A slush pile is the general mailbox or in the olden-golden days, the massive paper submissions a young (likely unpaid) intern sifted through in literary journal offices.

My work for example, the one essay that led to KHABAAR, Maacher Bazaar: Fish for Life, was picked up by Sari Botton, the then editor during the Christmas break. I was told by others not to submit during holidays and here was Sari working through one. So that’s myth one. The essay was a Notable Mention for Best American Essays in Food Writing, led to University of Iowa Press accepting my food narrative memoir, and my book being published in April 2022.

The myths are many. That submitting into a slush pile means you are lost. I’ve published in The Washington Post, Catapult, DAME, LA Times, New York Times, The Rumpus, Hippocampus and then made great connections with the editors and most of them ask me to submit to them directly. Donna Talarico of Hippocampus recently invited me to speak at their writing conference HippoCamp which is a full circle for me –so that’s another myth, that once you’re published, you move on. No, you don’t. You respect them for taking a chance on your work and you continue to build the relationship.

KARIN: How do you balance your career as a scientist and your life as a writer?

MADHUSHREE: I don’t. I work almost 12 hours on my day job which is global—and needs my attention at all times of the day (and night). I write in between. Sometimes 5-7 AM before the day starts. Sometimes 8-11 PM after everyone is asleep. Most times (pre-pandemic) on all long flights. I write on my phone (as notes) and transcribe. On email threads (to myself). Any which way to get the work done.

Don’t get me wrong, I love my day job. So it’s not like it’s a hindrance. This is life. No one said life was going to be easy. All you have to do is make it joyous and intentional in how you spend the time.

Buy the book

To learn more about Madhushree Ghosh visit her site.

See all interviews